In 1968, Chrysler shipped two brand new 1969 Charger 500s to Hot Rod magazine for a press preview. One was a B-5 Blue 500 equipped with a Hemi and a 4-speed. The magazine took the two 500s to a drag strip where the B-5 knocked off a quarter mile in 13.48 seconds.

Shortly after Hot Rod brought the cars back from the drag strip, the B-5 was stolen. Later, it was found in a bad neighborhood missing its Hemi, its interior and driveline. The write up in Hot Rod was nice but Chrysler could not repair and sell the B-5 car. They decided to turn it into an engineering test car. The shell was shipped as essentially a body in white to Nichels Engineering in Griffith Indiana.

Nichels rebuilt the car to NASCAR standards, including all of the knowledge Chrysler racing had developed for the Charger. They raked the body nose-down. They installed the bars inside the engine compartment from the firewall to the radiator support to stiffen the front end. They put in a roll cage, a race Hemi and matching drivetrain. Nichels then shipped DC-93 back to Chrysler. Incidentally, it was Nichels that designated the car DC-93. Indiana required cars to bear some sort of identification number and many of the cars in Nichels shop did not have VIN tags. Nichels simply numbered them sequentially with the letters designating the manufacturer and sometimes the model. DC stood for Dodge Charger.

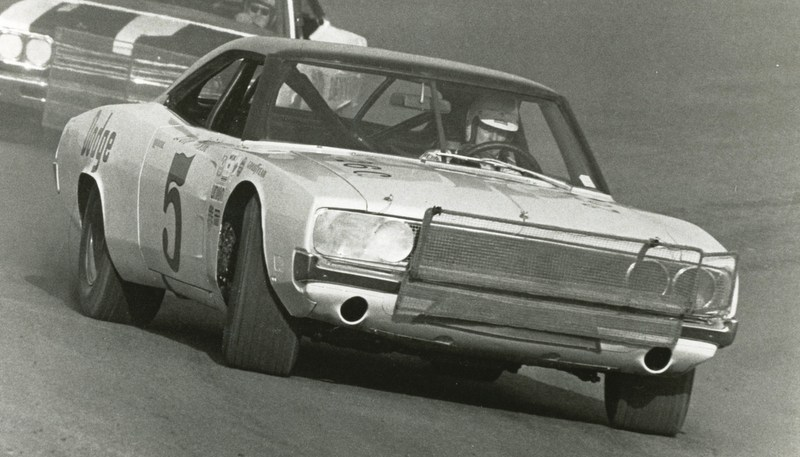

As the 1969 Daytona 500 approached, Chrysler racing engineers were certain DC-93 was state of the art. They painted the car blue and put #99 on it. They offered to let Nichels Engineering field the car for the race. Paul Goldsmith drove it. It did not run on pole day but NASCAR had gone to its dual qualifying race format. Goldsmith ran it in the second qualifier where Bobby Isaac, Charliet Glotzbach and Goldsmith completed a 1-2-3 sweep in Charger 500s. Things looked promising. DC-93 ran the fastest laps that weekend but crashed out of the main race on lap 62.

It was at this point that Chrysler decided to go to the next level and install the ultimate aero package the nose cone and the wing, making it a Charger Daytona.

All through 1969, DC-93 was used for testing the aero package. Many configurations were first tested on a low speed DC-74 and then tested on DC-93. Much of the testing was performed by NASCAR drivers like Charlie Glotzbach and Buddy Baker (above).

The team of engineers working on the problem now included rocket scientists from Chryslers missile division, some of whom had moved over and were working full-time on the aero cars. John Pointer fabricated and experimented with shapes of the nose cone and the wing at Chelsea. Bill Wright installed instrumentation on the cars, much as he would a rocket. Wright drilled a hole in the dashboard for the buttons and switch to control the instruments.

The test results convinced Chrysler higher ups to make the winged cars and sell them to the public so they could be raced in NASCAR. While Chrysler worked out the logistics of building the 500 cars necessary for the public, Chrysler racing made the wings and nose cones available to teams racing the Charger 500s. None of the teams would race actual Charger Daytonas; they would merely add the modifications to the 500s they were already running. The newly configured cars would make their first track appearance at Talladega in September 1969.

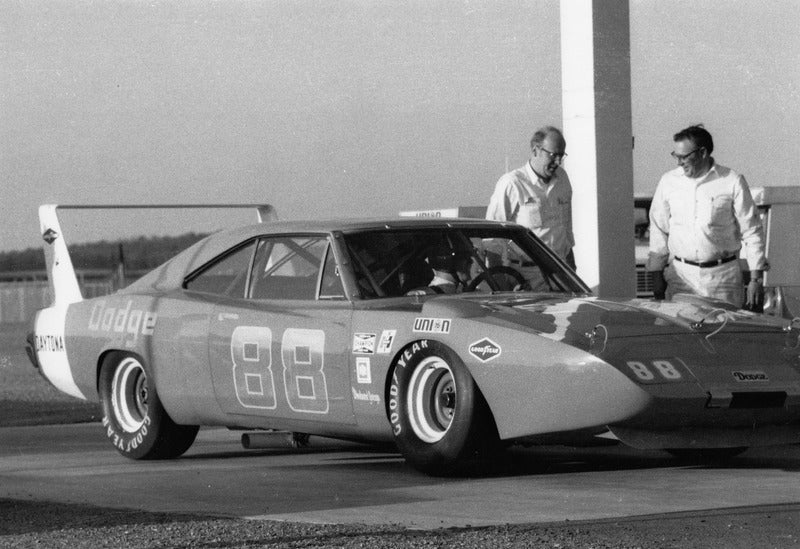

Larry Rathgeb brought DC-93 to Talladega for testing. Rathgeb would eventually bring DC-93 to every major track where the winged cars raced so Chrysler racing could gather its own data on setups for the cars. Once optimal speeds were achieved, the information was passed along to the race teams. Rathgeb feared that his creations would be shut out of the first big chance they had to race because of a threatened driver boycott. To make sure there was at least one wing in the race, he talked Nichels into entering DC-93 with Glotzbach at the wheel. Technically, a Chrysler-owned car could not race in NASCAR. As he had at Daytona, Nichels entered the car at Talladega as if he owned it. The car was outfitted to look like a Nichels-owned racer and the number 88 was applied to it.

The first day of practice at the track led to the headline: 200 MPH Certain At Talladega Track. Practice laps by Glotzbach and Isaac were faster than 195 MPH. Isaac was driving the K&K Daytona and Glotzbach was driving DC-93. The qualifying speeds were blistering. Glotzbach led the way in DC-93 at 199.466 MPH. He predicted he would be even faster on race day. He was slated to sit on the pole and then the Professional Drivers Association walked out. After reshuffling the starting lineup to account for the 30 drivers who were missing, Bobby Isaac was on the pole on race day. His 196.386 speed seems impressive NASCARs previous top speed had been set that July at 190.706 except that it had been slow compared to drivers who were sitting out the race. His qualifying laps were only sixth fastest at 196.386.

Richard Brickhouse won the race in another Nichels Engineering car not DC-93 leading a top-five sweep by Chrysler products. Only Brickhouse and Isaac were driving the new Daytonas, however. All of the other Daytonas at the track had been parked because of the boycott. DC-93 had sat the race out.

On March 24, 1970, DC-93 ran its transmission test where it broke 200 MPH with Buddy Baker at the wheel. The speed was a NASCAR record and world record for a closed course. After the Talladega record runs, the car was sent to Chelsea where Chrysler continued using it for tests.

For the rest of the 1970 season, Rathgeb continued bringing DC-93 to the major races where winged cars would run. A driver like Baker or Glotzbach would run practice laps with instrumentation in the trunk and engineers would crunch the numbers to find the best race setups for the cars at each particular track. DC-93 did not ever race again, however.

In May 1970, Bill France thought he might like to have DC-93 donated to the NASCAR Museum of Speed. He asked Chrysler if they were willing to donate it to his museum. It was an interesting question. Chrysler was still using the car but there were some people within the department who were less than happy with how France had treated Chrysler. France had never been all that welcoming to the winged cars and now he wanted one donated to his museum? There was already grumbling that France wanted to outlaw the winged cars altogether.

Chrysler racing also still had DC-74, the low-speed car from Chelsea which had been raced at one point as a 1968 Charger by Isaac. It had been given the Daytona treatment but was not being taken to NASCAR tracks for testing. It had been put out to pasture. Rather than commit to giving DC-93 to NASCAR, Chrysler decided it was more expedient to pull a fast one and donate DC-74, pretending it was DC-93. An internal memo described the plan.

[W]e will take our old No. 71 car, DC-74, paint it to look like the Engineering car No. 88 which was used in breaking the 200 mph speed record, and present it to NASCAR. This No. 71 car has outlived its usefulness and would be scrapped in the event we werent to use it for this purpose.

The memo noted the limited cost to Chrysler: paint and shipping. The upside: promotional benefits. The car will be of considerable interest in the future as a part of the overall speed museum. No explanation was given as to why NASCAR was being tricked. There is no question that some of the men who made the decision did it because they were unhappy with how NASCAR had treated Chrysler in the recent past. Years later, one of the men involved in the decision told this writer that the move was indeed intended as a way to give France the finger.

DC-74 was painted blue. In February 1973, at Daytona, a ceremony was held on the infield of the track to note the donation of the first 200 MPH car to NASCARs Museum of Speed. Chrysler vice-president Bob McCurry posed with France next to the car, along with Richard Petty and Buddy Baker. The shiny blue paint job hid the red paint on the former 1968 Charger.

Press releases of the event were distributed, accompanied by a confusing montage of photos. Along with the picture of McCurry, France, Petty, Baker and the car, there was one of a mock-up of a street Charger Daytona, white with a red stripe. Below that was a picture of DC-74, when it still wore red paint. The press release described the 200 MPH car which was not in any of the three pictures and the K&K car which set records at Bonneville. It, too, was not in any of the pictures with the release.

But that left the question: What happened to DC-93?

Don White was a driver best known for his USAC presence he was USAC champion in 1963 and 1967 and that circuits winningest driver with 53 victories he also raced occasionally in NASCAR for Nichels engineering. White was good friends with Chrysler racings Ronnie Householder and wondered what would happen to DC-93 after it had outlived its usefulness to Chrysler. Householder offered to give the car to White. White accepted and took delivery of the car in late 1970.

Because USAC allowed cars to be run for one more year than NASCAR, White could race DC-93 in its Daytona treatment through the 1971 season. Whites racing operation was not that big and he had to be a bit more economical. On a shorter track, he would remove the wing and the nose cone and run DC-93 as a Charger 500. A couple of times, he even raced the car on dirt. Then, when he went to a bigger track, hed reinstall the nose cone and the wing.

When the 1971 season ended, DC-93 could no longer run as a 1969 model. For the 1972 season, White removed the wing and also the front fenders and nose cone, which were welded together. He dumped the front end sheet metal in the weeds behind his shop. He put a 1970 Charger front clip on the car and raced it, even though the back window was wrong. NASCAR might not have allowed that but USAC didnt complain. He raced his 1970 Charger for a couple of years in USAC.

He completely reskinned the car as a 1973 Charger when the 1970" could no longer run. The later year Chargers were a bit wider than the 1969 Charger, so he had to finesse the sheet metal to make it fit. After a few more years of racing, he parked DC-93 by his shop and left it.

A Chrysler technician named Greg Kwiatkowski was fascinated by Chryslers racing legacy and often asked his coworkers about their knowledge of the companys history. He spoke with Rathgeb and others who had been instrumental in the field. One day, Rathgeb mentioned to Kwiatkowski that the 88 car at the NASCAR museum was not the 200 MPH engineering car.

Where was the real DC-93? He eventually heard that Householder had given it to Don White. Kwiatkowski called White, introduced himself, and asked if he knew what happened to the car. Of course he did; it was sitting right outside his shop.

White described the car to Kwiatkowski and told him how it was now configured as a 1973. It had been parked since 1976 but was not for sale. Kwiatkowski told him that was fine; he was happy to learn as much as he could about the car and that it survived. He stayed in touch with White and during one conversation, White asked Kwiatkowski what he thought the car was worth. Kwiatkowski said he had no idea but if White ever sold it, hed be happy to buy it. How much did he think it was worth? White said after noting that the car was still not for sale - $5,000. Kwiatkowski told him he thought it was a fair price and to keep him in mind. A few months later, White offered to sell him the car.

Kwiatkowski had no doubt the car was real but he realized he had no idea what the car looked like. He asked White if he would take some pictures of it for him. He sent down some disposable cameras and some money for postage so White could mail them back. Kwiatkowski told him to just take as many pictures as he could of it. A short while later White sent back the cameras, along with the change from the money Kwiatkowski had sent for postage. After developing the film it was clear: the car was in rough shape but it was the right car.

Rathgeb had given him photos from the 200 MPH run and Kwiatkowski scrutinized them alongside the pics hed gotten from White. Key details matched. The main hoop of the roll bar had flaking paint, underneath was blue paint. Kwiatkowski called White back and said they had a deal. He offered to send him a deposit even though White said it wasnt necessary. He sent a money order for $500 and began making arrangements to get the car.

When he got to Whites Iowa shop three weeks later, White told him that another person had come by shortly after they had struck their deal and offered him $10,000 for it. Don told the man the car was already sold. The car was in rough shape from sitting outside. It was 1998 and the car had been outside for more than twenty years.

Kwiatkowski asked White if he had any of the old parts for the car. White suggested checking the woods out back. There, he found the front clip. The fenders and nose cone were welded together and now plants were growing up around them. It took four men to haul it out. It was awkward and heavy, more so because animals had stuffed the nose cone full of nesting material. Kwiatkowski trailered the car back to Michigan and began the long task of dismantling and restoring the car. In 2001, the Aerowarriors held a reunion for winged car enthusiasts in Auburn Hills, Michigan. Kwiatkowski attended as did Rathgeb, Pointer, George Wallace and a few others who had worked on the program. He invited the men to his garage to see DC-93. There, they saw the car dismantled the 1973 body panels were removed but they recognized it. Wright recognized the hole he had cut in the dash for his instrumentation.

George Wallace was kind enough to draft a letter of authenticity for Kwiatkowski. Although all of the men positively identified the car, Wallace was a good candidate for the letter. He had been at Talladega to see Glotzbach qualify the car and then at the track when Baker broke 200 MPH. He also spent time inside the car as a passenger, sitting on the floor and writing notes while clinging to the roll cage as the car ran at speed on various tracks.

Kwiatkowski is now in the process of a full restoration of the car to its configuration as it was on the day it broke the 200 MPH mark at Talladega. He has even located an engine which can be documented as having been used at one time in the car during its time with Chrysler. Meanwhile, NASCAR still has DC-74 in its collection. It is still painted blue.

Story by

Steve Lehto

updated by @johnny-mallonee: 12/05/16 04:00:58PM