Mike Hembree wrote a great article on Sterling Marlin's on-going racing and challenges with Parkinsonism disease.

http://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nascar/2014/09/16/sterling-marlin-has-parkinsonism-still-driving-nashville/15652705/

The story doesn't visit much of the past but instead focuses on Sterling's current racing endeavors and health situation. Included in the article are a handful of really funny quips.

Sterling Marlin races on despite Parkinsonism

NASHVILLE, Tenn. Among former NASCAR driver Sterling Marlin's many friends in auto racing circles is a man whose nickname is Shaky. Shaky has Parkinson's disease.

"I was in my motorhome at the track one time, and Shaky came in," Marlin told USA TODAY Sports. "I was eating a bologna sandwich, and I asked him if he wanted one. I fixed it and handed it to him. He sat there holding it with his hands shaking and moving back and forth, and he was trying to grab the bologna with his mouth. I said, 'Shaky, it looks like you're having some trouble.' "

Years later, Marlin has a much clearer understanding of Shaky's dilemma. Two years ago, Marlin was diagnosed with Parkinsonism, a degenerative nerve disorder similar to Parkinson's. His right hand shakes involuntarily, and he has a slight limp in his right leg.

Yet Marlin, 57, hasn't put down the tools of his trade a race-car steering wheel and the associated wrenches, torches and hammers that accompany the ride.

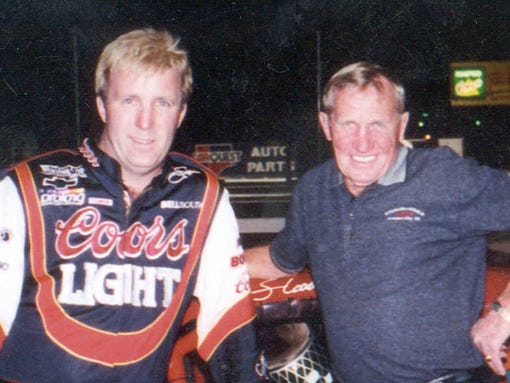

On a hot summer Saturday night at Fairgrounds Speedway in Nashville, the track where Marlin got his start under the guidance of his father, the late Clifton "Coo Coo" Marlin, he's back burning laps on the .596-mile surface. Five years removed from his final race in Sprint Cup, a series that made him a rich man, Marlin is a hobby racer again, banging fenders just for the fun of it.

He races regularly at the Fairgrounds, a classic Southern short track that, like Marlin, is a survivor. Sitting in the shadows of the tall buildings of Nashville's modern cityscape, the speedway is a stubborn anachronism. Some city leaders want the track, which formerly hosted the Sprint Cup Series, demolished to allow for expanded development of urban Nashville, but, like Marlin, it races on.

Marlin won the Fairgrounds track championship in 1980, '81 and '82 as part of resume building that eventually put him at the top level of Sprint Cup racing. He won 10 times, including back-to-back Daytona 500s in 1994 and '95, and became a championship challenger. When injuries and sub-par rides brought on the decline of his Cup career, Marlin surprised almost no one by returning to Nashville, an hour north of his sprawling farmstead in Columbia, Tenn., to race once more.

Marlin: 'I can do what I need to do'

Son of a racer and father of one (and, not incidentally, father-in-law of one), Marlin carries the vigorous gene that seems to make turning fast laps in competition almost a necessity. Even with a debilitating health condition.

Parkinsonism causes a combination of the movement abnormalities that are typical in Parkinson's disease, such as tremors and impaired movement, and often ushers in Parkinson's. Although Marlin said it has not diminished his ability to work on race cars and drive them at high speeds, the impact is obvious to anyone who follows him around the Nashville pit area. His right hand often shakes, and he works on his race car primarily with his left hand. A natural right-hander, he writes slowly.

"When it first started, I couldn't fasten my helmet or button a shirt with my right hand," Marlin said, "but now I can do what I need to do. I take the medication, and that pretty much controls it. It doesn't have any impact on driving. My hand doesn't get tired. I drive mostly with my left hand, anyway. My right hand kind of floats along with the steering wheel."

People noticed the change, though. Retired three-time Cup champion and current TV analyst Darrell Waltrip, who also won Nashville track championships, said Marlin's problem became evident as they communicated via phone.

"It got to where he couldn't text back and forth with me," Waltrip told USA TODAY Sports. "That was the way that we would communicate, but, over a period of time, I couldn't tell what the text messages were. He finally told me to call him, that if I wanted to talk that's what we had to do. That kind of worried me."

But Waltrip raced through a laundry list of injuries in his Hall of Fame career and understands the urge to keep racing.

"You can have some physical problems, but if it's in your genes and you have the talent like Sterling has, those things don't seem to affect you like maybe they would other athletes," Waltrip said. "I had broken ribs or a broken collarbone, but when I got in my race car I put all of that out of my mind and focused on the driving and still did pretty darn good.

"I think it's probably great therapy for him to go out there and compete. The other things kind of go on the back burner."

Marlin led about half the 100-lap race on this Saturday night, finishing second after his Chevrolet developed minor handling problems in the closing laps. He runs in every race at Nashville, where the schedule is limited to one event per month, and also occasionally competes in Late Model races at other big regional tracks outside the Southeast. He remains a box-office attraction.

Building a life around racing

Marlin is on a far shore from Cup now, but that hardly seems to matter. It's about the racing. Always has been.

"We had to get married around racing, and we still plan everything around racing," said Paula Marlin, Sterling's wife of 36 years. "It's just always going to be that way. It never changes. He still drives crazy, and he still drives everybody else crazy."

Paula is in the infield on this night. Steadman, Sterling's son, works on the team's pit crew. Sutherlin, Marlin's daughter, has brought her one-year-old son, Colter. Sutherlin's husband, Michael House, also races at the track.

Steadman's 10-year-old son, Stirlin, already is involved in the family's racing, his duties primarily involving cleaning the inside of the race car and eating potato chips from the stash in the team truck. His grandfather figures he'll soon buy Stirlin what is defined in the Marlin vernacular as a "yard car," a beat-up $100 junkyard refugee that the boy can spin in the dirt on the farm. This is the first step toward racing, if Stirlin wants that.

The cycle goes on.

"I'll be doing this until I can't any more or until I don't want to or can't compete," Marlin said. "We still lead laps and can win races, so I'm still enjoying it."

The Marlin compound, as the family calls it, stretches for 850 acres south of Nashville, and he raises beef cattle. Marlin claims to be half-racer, half-farmer.

Sutherlin, however, disagrees. "He's seven-eighths racer, one-eighth farmer, maybe," she said.

Although Marlin's sweeping farm acreage is impressive and the house he and Paula built 18 years ago dominates the landscape, the race shop along the roadside clearly is Marlin headquarters. He owns five Late Model cars. He, Steadman and House would choose tinkering on the cars over riding tractors across the hay fields (although Marlin admits that, after a wet summer, "It's time to cut hay.").

Marlin always has been a combination of farm boy and racer. He knows the surrounding woodlands well and can take you to the old oak tree where he and his teen-age pals hid their copies of Playboy . His father grew tobacco, and Sterling worked those fields as a teen-ager, providing significant incentive for a racing career.

"I don't miss that a bit," he said. "Tobacco is a 13-month-a-year job. It's a lot of hands-on labor. Hot. Nasty. Sticky. A mess. I don't know how my dad did that and raced, too."

Success in racing turned Marlin into a gentleman farmer of sorts, although he still likes to climb on a tractor now and then. The money that flowed from Cup victory lanes allowed him to buy and develop property in and around Nashville, and he and Paula own a condominium in St. Thomas. They visit there several times a year, but, as Paula points out, "The visits keep being cut shorter and shorter because we have to get back to work on a race car."

This, despite the nagging realities of Parkinsonism.

'It was scary'

Marlin said he first noticed something unusual about his health three years ago.

"I'd be walking and kind of trip like my right leg wouldn't pick up the foot enough," he said. "And I would have trouble starting to thread a nut with my fingers. Then I cut a knuckle on my right hand bad cutting some exhaust pipes. Opened it up pretty good. But I closed it with some Super Glue. Didn't have time to go to the doctor. Had a race the next day."

This clinical approach is not unusual in the Marlin family, Paula confirms. "Super Glue and duct tape," she said. "He couldn't live without duct tape."

Marlin eventually did visit a doctor, however, and the Parkinsonism was confirmed. He's on three-times-a-day medication to help control the tremors.

"The doctor said it could get worse or it could stay like it is for 15 or 20 years," Marlin said. "I went this week to see him again, and he said everything looks fine, that I can stay on the lowest dosage medicine."

As he has for most of his life, Marlin accepted his health issue as just another bump in the road and drove on. The word "Parkinson's" brought the extended Marlin family to attention, though, said Jon Hood, Paula's younger brother and a member of the Marlin racing crew.

"It was scary," Hood said. "You hear Parkinson's, and naturally you think, 'That's it.' My grandfather had the full-on Parkinson's, so I know what it will do to you. But Sterling is a tough cat. You'd never know from him that it bothers him. What you see is what you get. At times it gets frustrating, but he's not going to use it as an excuse or a crutch or anything.

"I told my family last year that they better come to all the races they can because this could be it, but then he won three of the first four races last year, and it lit a fire under him. He keeps buying more cars. I think he'll race until he can't get in the car any more."

Tony Formosa, the Nashville track operator, a former driver and a long-time friend of Marlin's, understands. Formosa, now 60, lost his left eye in a track accident at 17 and decided to give up his dream of racing.

"Then one of the champion drivers here at the track, George Bennett, came out to my house," Formosa said. "We sat on the patio, and he asked me, 'When are you getting your car and coming back to the track?' I said, 'Well, I won't be back. I knocked my eye out.'

"He took off his glasses and said, 'Look here. I lost my left eye when I was 3 years old. It was pecked out by a chicken. It didn't stop me from driving.' That inspired me, and I came back to accept the challenge.

"You just keep doing what you love to do. You make the best of what you've got. Even though Sterling has some health issues, it doesn't look like he's ever skipped a beat. He's just as sharp on his setups. He knows where he's going when he starts something, and it takes a lot to throw him off track. He's still a hell of a race car driver."

'The thing about Sterling - he never changes'

Saturday is a long race day at Nashville. Teams check in by 11 a.m. Daylight hours are filled with practice, qualifying and races for undercard divisions before the featured Late Models run about 9 p.m.

Family and crew members are one and the same for most of the teams in the pit area, and there is near-constant traffic in the Marlin hauler from the race car parked outside to the rear of the team hauler, where tools, Gatorade and sandwich bread are stored.

Hanging near the back of the hauler is a baseball bat, which one of the team members describes as an "encourager" if disagreements between teams or drivers erupt. "It wound up here one night after a fight, and we kept it," Marlin said, smiling.

Talk in the hauler includes University of Tennessee football (for it), immigration at the Mexican border (against it) and the track hot dog (for it).

Billy Harrison, friends with Marlin since the second grade, works on the pit crew, along with his sons, Zach and Luke. Another son, Nick, also has a background at the Nashville track but now is a crew chief for Richard Childress Racing.

Billy Harrison, who played football with Marlin at Spring Hill High School in Columbia, has watched every step of Marlin's career.

"The thing about Sterling he never changes," Harrison said. "He's been the same down-to-earth country boy. Once he retired from NASCAR, this racing here is all about fun. This was the track he grew up on, and he loves to race here. That's what it's all about to him."

Marlin qualifies fourth fastest in a field of 28, takes the lead on the third lap and stays in front until lap 50, when eventual winner Josh Weston moves in front. "Car just got loose," Marlin says after the race.

Marlin signs autographs for fans, his right hand shaking. Still "country as cornbread," as one of his friends says, he will ride off into the Nashville night to race another day.

"No one cuts him any slack on the race track," said Nashville driver Tyler Miles, 22 and a Marlin fan since childhood. "He's still a racer. He's one of the ones to beat. He's one of us."

--

Schaefer: It's not just for racing anymore.

updated by @tmc-chase: 12/05/16 04:09:31PM