PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

"Fifty-five dollars, 55, 55," the auctioneer barks, "54, 53, 52, 51– do I have 50?"

Pipe smoke occasionally drifts through the thick air, momentarily disguising the unmistakable odor of livestock. From the faded blue wooden bleachers and the sea of mostly middle-aged men, a single tan hand rises.

"51, 51, 52, 53"– the bidding slowly rises on a calf in a dusty pit, and the regular cadence of quick numbers is broken only by the occasional mooing of other cows waiting their turn. When bidding stalls at $64, the auctioneer's voice falls slient, and the calf heads to its destiny through a large door at the back.

This is how the Charlottesville Livestock Market has operated for more than 60 years, and this is the heart of Hogwaller.

Hogwaller: a remnant of Charlottesville history with a cloudy future.

In the face of the City's effort to distance itself from the name, only echoes remain. There's a band called the Hogwaller Ramblers, there's a home-grown beer called Hogwaller Kolsch, and there's a diner on West Main Street whose menu offers Hogwaller Hash.

It's a name that doesn't appear on any map, and it's one that some city officials wish would go away. And while for people who grew up there, Hogwaller has a special meaning, not all those memories are warm.

Sticks and stones

"I grew up there," said Gene Cassidy, who was raised at 811 Rives Street. "We had a nice, clean, neat home that we were proud of." But Cassidy, who died a year ago at the age of 74, felt the sting of snobbery on his daily walk to school. Along the way, he said, he and other students would hear jeers: "Here come the kids from Hogwaller!"

"It made you feel very small," Cassidy said. "It made you feel very self-conscious."

Cassidy explained that while white city kids could walk to the various downtown schools, his family– due to mid-century annexations in 1938 and 1963– had to travel two miles each way to Lane High School, today the County Office Building on McIntire Road. Hogwaller, he noted, "didn't even have sidewalks."

But pride and infrastructure aside, Cassidy said that one thing was sure: "The name really attracts attention."

Overton McGehee, the local director of Habitat for Humanity, has experienced first hand the kind of reaction the Hogwaller name can provoke. When Habitat bought Sunrise Trailer Court in the heart of Hogwaller several years ago, McGehee says, he was warned by people at City Hall to avoid the H-word.

"City officials told me not to use the name," he says. "They said, 'That's north Belmont.'" (It's actually located southeast of much of Belmont.)

City spokesman Ric Barrick says he can easily explain the warning: "It's more of a derogatory name that we would not endorse because it's classist," he says. "'Belmont' is the current terminology."

As far as history is concerned, Barrick says Hogwaller was never an official name: "It was a name that was used both positively and negatively by people, depending on what side of the tracks they were on. But it was never officially sanctioned."

Memories of a community

On the front porch of a house with white siding and brown trim, a man with a deeply lined face sits watching a cement truck rumble by. His rolled up jeans clash only slightly with an earring sparkling in his left ear.

"When I was growing up, you didn't see many cars," says Andy Lawson. "If you saw two cars all day long, you were a lucky damn man."

Lawson has lived his whole life between the sleepy streets of Rives and Nassau, in what he refers to as "the bottom," the lowest terrain of Hogwaller that backs up to the flood plain of nearby Moore's Creek. Born in 1939, Lawson is a member of an authentic Belmont industry bloodline: his grandmother worked at the nearby Woolen Mills, both his parents worked for the Frank Ix textile company on Elliott Avenue, and Lawson himself worked at Barnes Lumber adjacent to the Belmont Bridge.

One of seven children, Lawson grew up when Hogwaller was more country than city: he remembers when Franklin Street was nothing but gravel and tar, when the site of Rives Park was half cornfield/half cow pasture, and when the city limits had yet to totally cross the quiet neighborhood.

"It's hard to keep up with people nowadays," the retired construction worker says. "You don't know your neighbors anymore."

And he finds himself faced with other modern problems; his family says street racing occurs regularly on their block, and they suspect drugs and violence are present in their once-placid community.

Lawson bought his current house at 914 Nassau Street just across from what is now Rives Park for $4,000 in 1969. Today the ritzy Linden Town Lofts condominiums– starting price $249,000– are just a stone's throw away, and his parcel now has an assessed value of $120,000.

"This little house has withstood a lot," Lawson smiles. He has raised four kids, two sisters, and a grandchild there.

Over the years there's been lots of positive change, but Lawson says destruction has also taken its toll. Though he says he's pleased with improvements in infrastructure and new opportunities for kids in the neighborhood, he's outraged over the recent removal of the Woolen Mills dam. "It should have been history," he says, his voice rising in anger. "It ain't no different than Jefferson's place."

And though he's proud of where he's from, Lawson sees more value in people than in places. "It don't make no difference where you live," he says. "It matters what you want to be. Life is what you make it."

Keeping the 'hog' in 'Hogwaller'

It's the first Saturday afternoon in September, time for the weekly auction at the Charlottesville Livestock Market. Old advertisements for farm equipment and Chevy trucks cover one wall of the dilapidated, but still very much operational, arena.

In the dusty pen below the bleachers, a man in a pristine white cowboy hat, sporting a mustache, a massive belt buckle, and mud-encrusted work boots, leans on a long green stick, occasionally wielding it to prod a white calf with black ears, nose, and feet.

"324-pound bull calf," the auctioneer calls out.

On a walled platform just above stand two men, one with a microphone and one with pen and paper. A small wreath of flowers hangs just above a sign, "Auctioneering by Dick Whorley."

The Charlottesville Livestock Market sits at the bottom of the steep hill cradling the neighborhood between I-64 and Belmont, overlooked by a sea of single-story concrete bungalows from the 1940s and '50s, many with verdant views of Monticello Mountain. Closely packed trailers line a lot across the street.

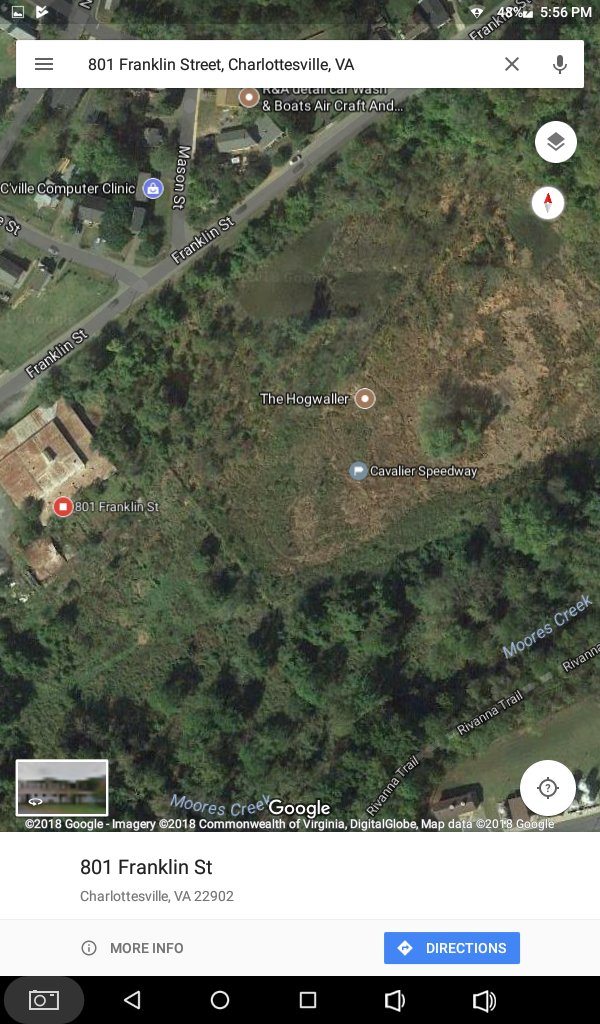

The livestock market got its start on Garrett Street in the 1800s before moving just southeast of Douglas Avenue, along the bustling C&O rail yard the City converted to an office park in the late 1980s. It moved to its current site at 801 Franklin Street in 1946.

Owned by John H. Falls since 1980, the Charlottesville Livestock Market still holds auctions every Saturday, and at least once every five years or so, an animal escapes. But cows and pigs aren't the only things that have played in the Hogwaller mud.

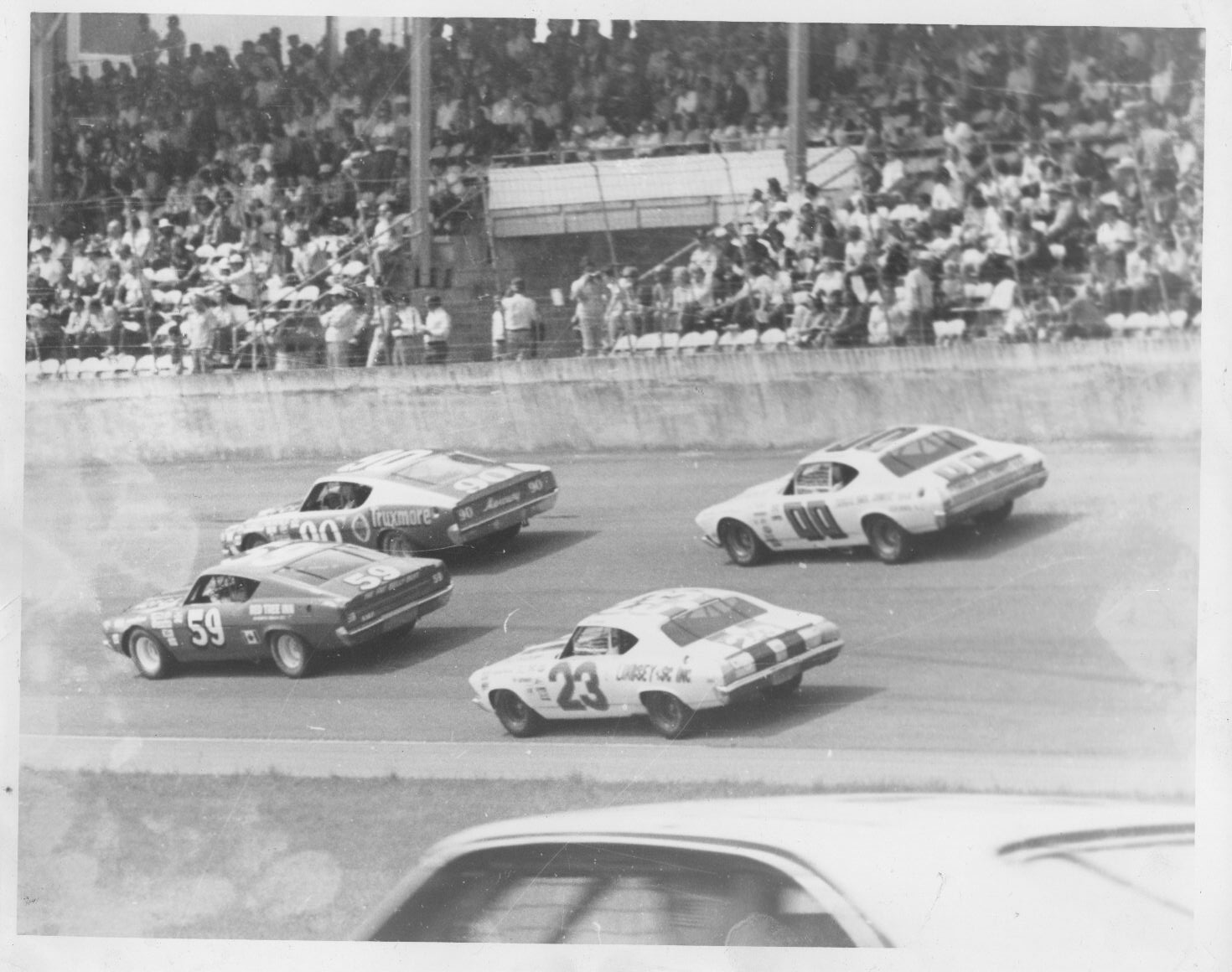

A vacant field between the Livestock Market and the creek was home for a while to Charlottesville's first and last stock-car track, owned and operated by George Durham. Cavalier Speedway was a quarter-mile dirt oval track that seated about 3,500. It opened on an overcast April evening in 1954, when Orange County's Bob Dobbins won the 25-lap race, cheered on by a full house.

One of many tracks appearing across the South at the time, the venue also featured wrestling matches, turkey shoots, and daredevils. But the Speedway's glory was short-lived, and it closed after just two years. Today, the site remains an empty field.

Orange County's Bob Dobbins won the opening race at the Cavalier Speedway on Friday, April 23, 1954, and made the front page of the Progress the next day.

ARCHIVE IMAGE